Calluses Over Cushions: Why We’re Raising a Generation of Fragile Adults

The playground used to be a lesson in gravity. Now it’s a lesson in liability. We stopped letting kids fall, so now they’re breaking inside. Here’s how we fix it.

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

You can tell a lot about a civilization by its playgrounds.

When I was a kid, the playground was a lesson in physics and gravity. It was asphalt, metal slides that would sear your legs in July, and monkey bars high enough to break an arm. Today? It’s rubberized flooring, rounded plastic edges, and warning signs. It looks safe. It feels safe.

But if you look at the data, we haven’t made our children safer. We’ve just traded broken bones for broken minds.

We’re engineering a generation of children who have never felt the sting of a scraped knee or the hollow ache of true boredom. We call it “protection,” but let’s call it what it is: atrophy. We’re raising kids in a sterile lab environment and then acting surprised when they collapse upon contact with the dirty, chaotic reality of the world.

It’s time to stop preparing the road for the child and start preparing the child for the road.

Resilience is not a personality trait; it's a callus built through exposure to manageable stress. To raise capable kids, we must prioritize competence over safetyism. The data shows that unsupervised play and manual literacy reduce anxiety, while over-protection fuels it.

The Receipts: The Cost of Safetyism

I don’t deal in feelings; I deal in what’s happening on the ground. And the ground is shifting beneath our feet.

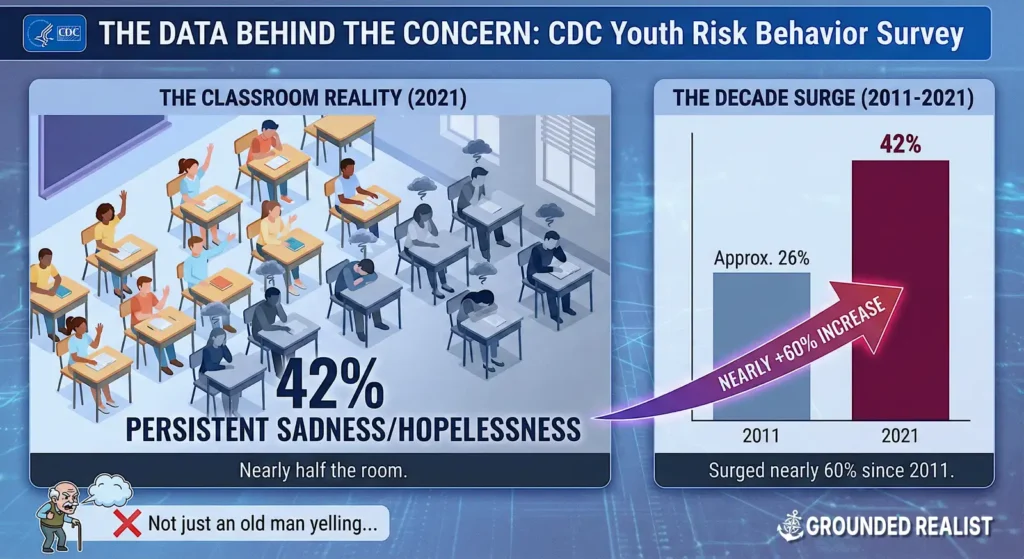

You might think I’m just an old man yelling at clouds, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has the numbers, and they are terrifying. In their 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, they found that 42% of high school students experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness. That is nearly half the room. That number has surged nearly 60% since 2011.

Why 2011? That’s the year smartphone penetration crossed the 50% threshold.

But it’s not just the phones; it’s the loss of independence. Dr. Peter Gray, a research professor at Boston College, has spent decades studying the decline of “free play.” His research, published in the Journal of Pediatrics, draws a straight, undeniable line between the decline of unsupervised activity and the rise of youth psychopathology.

We stopped letting them walk to the store. We stopped letting them resolve their own arguments in the backyard. We intervened. And in doing so, we robbed them of the only thing that builds self-efficacy: the evidence that they can handle a problem without Mom or Dad swooping in like a heavily armed helicopter.

“But the World is More Dangerous Now”

I hear you. You’re reading this and thinking, “That’s easy for you to say, but you don’t live on my street. I can’t just open the door and hope for the best.”

And you’re right. Blind optimism is just as dangerous as blind paranoia. I’m not saying ignore reality; I’m saying assess your reality, not the one sold to you by the 24-hour news cycle and social media fearmongers.

The macro data is clear: According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program, the violent crime rate in the United States fell by approximately 49% between 1993 and 2019. The world is objectively safer today physically than it was when we were riding bikes without helmets until the streetlights came on.

However, statistics don’t walk your kid to school. You do. You know your neighborhood. You have to decide what’s right and act accordingly.

The goal isn’t to throw them to the wolves; it’s to lengthen the leash intelligently, and age-appropriately. It’s about Graduated Competence.

- Audit your actual environment: Is your neighborhood actually dangerous, or does it just feel dangerous because of what you saw on Twitter?

- Test and verify: Don’t just send them out. Walk with them. Watch them navigate the crosswalk. Verify they have the skills before you grant the freedom.

- The “Spotter” Method: Let them lead while you shadow them from a distance. Give them the autonomy of the experience with the safety net of your presence, until the safety net is no longer needed.

- Teach the Hazards: We were instilled with grave advice by our elders back in the day who took the time to ensure we were streetwise – “don’t talk to strangers” – being one that springs to mind. They weren’t dumb, they faced the same fears we did, but they did it anyway.

We aren’t asking for negligence. We’re asking for a calibration of fear based on facts, not feelings.

The Reality Check: Deconstructing the Boogeyman

Let’s look at the two biggest fears keeping kids strapped in the backseat: “The White Van” and “The Bumper.”

1. The “Stranger Danger” Myth

You’re terrified of a stranger snatching your child off the sidewalk. That fear is visceral, but the numbers do not support it. According to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), non-family abductions make up only 1% of missing child cases.

The vast majority of missing children cases are runaways or family abductions (custody disputes). “Stereotypical kidnappings”, where a stranger takes a child overnight or transports them 50+ miles, are statistically incredibly rare, occurring only 100-300 times a year in a country of 73 million children.

You’re more likely to be struck by lightning than your child is to be taken by a stranger on the way to school.

2. The Traffic Myth “But the cars are faster now.”

Despite the rise of SUVs, the roads have become safer for pedestrians over the long arc. According to Safe Kids Worldwide, the pedestrian fatality rate among children decreased by 32% between 2004 and 2018. Even recent NHTSA data shows child traffic fatalities dropped another 10% from 2022 to 2023. The danger is manageable, especially when you use the tools available.

3. The Government Solution (That Actually Works)

You don’t have to go it alone. The Safe Routes to School (SRTS) program is a federal scheme specifically designed to fix this. They provide funding for better crosswalks and signage, but more importantly, they champion the “Walking School Bus.”

This is a simple, tactical solution: one or two parents walk a group of neighborhood kids to school, picking them up along the route. It provides the “safety in numbers” that mitigates traffic risk and completely nullifies the stranger threat, while still getting the kids outside, walking, and socializing before the bell rings.

But if that’s still too much, it’s OK. You’re the parent, you decide. There are plenty of other ways to help them build confidence from our current low bar position:

Competence is the Antidote to Anxiety

Anxiety is often just a lack of competence. It’s the brain signaling, “I don’t know if I can handle this.” The only way to silence that signal is to prove to the brain that, actually, I can handle this.

We need to stop validating every emotion and start validating skills. When a child falls, you don’t rush over and curse the ground. You watch. You wait. You let them assess the damage. You let them stand up. That moment of hesitation—that split second where they realize “I’m not dead”—is where the callus forms.

The Brass Tacks Fix

We need a return to “Free-Range” competence.

- Delay the Digital Onset: No smartphones before high school. Give them a dumb phone if you need to track them. The data from Jonathan Haidt’s research in The Anxious Generation is irrefutable: social media is an envy engine that shreds self-worth. Cut the cord.

- The “Walk Away” Rule: If they’re old enough to read a map, they’re old enough to navigate the neighborhood. Start small, but expand their radius.

- Manual Literacy: A child who can change a tire, cook a meal from raw ingredients (not a box), and fix a running toilet is a child who knows they have agency over their environment.

Take your kid to the garage, the garden, or the kitchen. Pick a task that is slightly too hard for them. Maybe it’s building a birdhouse, maybe it’s starting a charcoal fire.

Don’t do it for them. Don’t correct them before they make the mistake. Let them struggle. Let them get frustrated. Let them get their hands dirty.

When they finally figure it out – and they will, if you get out of the way – look at their eyes. That light you see? That isn’t happiness. That’s dignity.

We don’t need more “happy” kids. Happiness is fleeting. We need capable adults. And capability is forged in fire, not wrapped in bubble wrap.